- Cognition /

- Clever Dog Lab /

- Current Projects and Publications /

- Canine Theory of Mind?

Dogs read the behavior of humans without seeing them

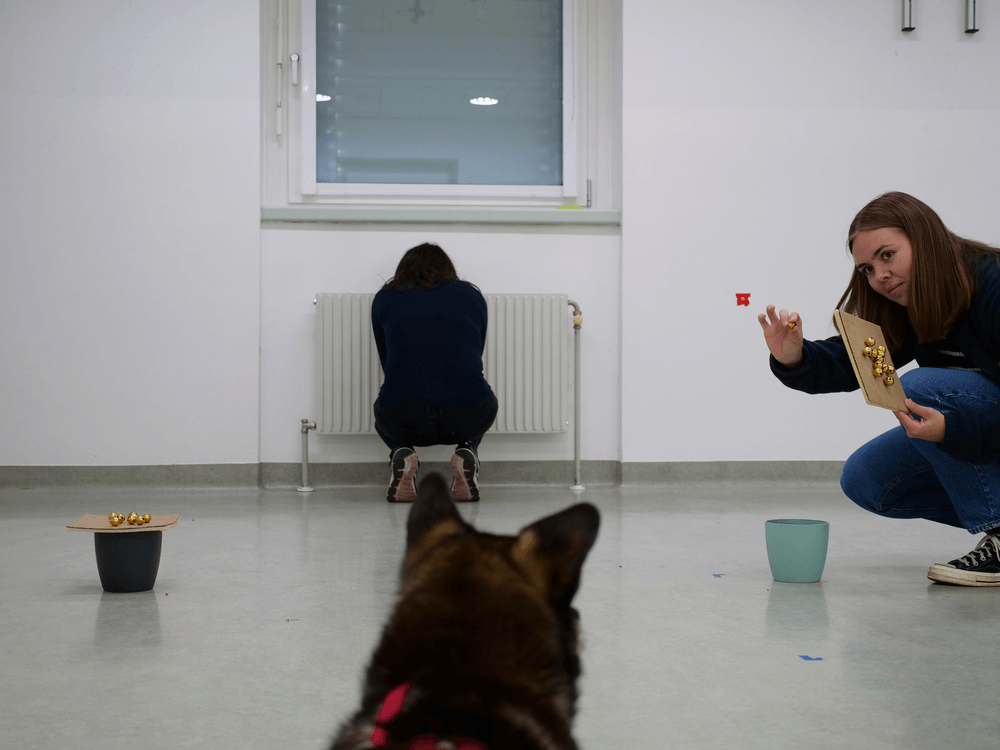

Dogs have remarkable abilities to interact with humans. A new study at the Clever Dog Lab adds another piece to the puzzle of our knowledge about these special cognitive abilities. The researchers used a test to investigate the extent to which humans are capable of perspective-taking when they cannot observe the behavior of the person they are trying to understand. In the decisive test, the human was not even in the room. The result is clear: around three quarters of the dogs tested drew the correct conclusion, even though they did not see the human, but only imagined them.

Publication: iScience

Can dogs distinguish between people with true and false beliefs?

In an earlier study we found that dogs react differently when human informants have true or false beliefs about the location of a treat (Lonardo et al. 2021). Now we wanted to know whether dogs could also make this distinction in a non-verbal change of location task when they could observe humans who could not see what was happening (the food was hidden and then moved) but could hear it in one condition (true belief, the movement was loud) and could not hear it in another condition (false belief, the movement was silent). This study was presented by Lucrezia Lonardo at the Canine Science Forum 2025 in Hamburg and is currently under review in a scientific journal. One diploma thesis (Victoria Berndl) discussed preliniary results, another one (Gina Risch) investigated potential breed type differences in this auditory false belief task. One research project of one of the IMHAI students (Camilla Haider) also focused on this study.

A follow-up study investigating potential breed differences in this task will be conducted by a student of Applied Biology (Sam Dassen) coming from the HAS Green Academy (the Netherlands) and a vet student from Vetmeduni Vienna (Jana Sebestyen).

The construct validity and test-retest reliability of perspective taking in dogs

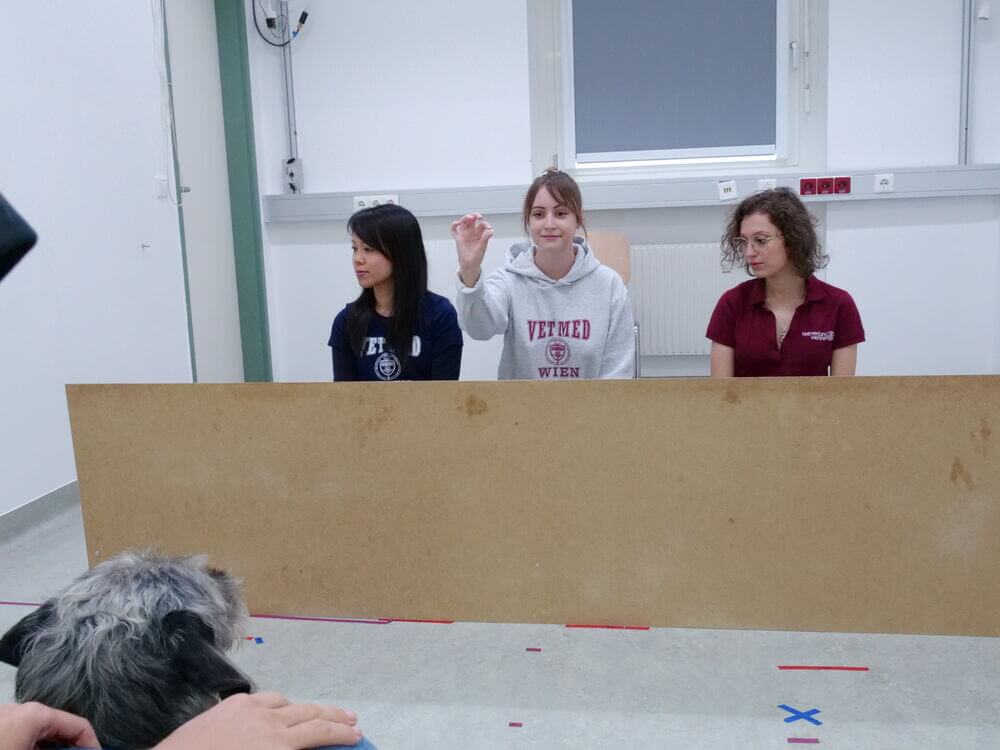

In this study we examined (a) the construct validity and (b) the test-retest reliability of perspective taking in dogs. The first measures whether our tests can reasonably be considered to reflect the intended construct – perspective taking, while the second measures test consistency, the reliability of a test measured over time. A methodology that has been used to test dogs' ability to take the perspective of others is the “Guesser-Knower” paradigm.

Previous studies found that dogs can discriminate between informants that have seen the baiting of food (Knower) or not (Guesser) (Maginnity & Grace 2014; Catala et al. 2017). However, the sample size of these studies was small (N=16), and dogs performed better in some conditions than in others. In this study, therefore, we used a much larger sample size (N=94). We obtained results that only partially replicated previous findings. This study is part of a Master thesis at the Université Sorbonne Nord Paris (Sarah Verrart), a Master thesis at the University of Strasbourg (Flore Luttmann), an internship of two students from the Netherlands (Jacco Spithout and Jannes Dommisse) and the Diploma theses of two vet students from our university (Nina Dygryn and Hannah Veitl). A volunteer (Phuong Thu Nguyen) also helped with data collection during an internship.

Investigating pet dogs’ and human infants’ altercentric bias with eye-tracking

Perspective taking through experience projection

Dogs follow human misleading suggestions more often when the informant has a false belief

Dogs do not use their own experience with novel barriers to infer others’ visual access

People involved:

Univ.-Prof. Dr.rer.nat. Ludwig Huber

T

+43 1 25077-2680

E-Mail

Dr.rer.nat. Christoph Völter

T

+43 1 25077-2670

E-Mail

Lucrezia Lonardo, PhD.

E-Mail

Ass.-Prof. Priv.-Doz. Stefanie Riemer, PhD.

T

+43 1 25077-2698

E-Mail

Laura Laussegger

E-Mail

Marion Umek

E-Mail

Sarah Verrart, MSc.

E-Mail

Nina Dygryn

Hannah Veitl

Sam Dassen

Jannes Dommisse

Jana Sebestyen

Ester Ganzenbacher