- Home /

- University /

- Infoservice /

- Press Releases /

- Beyond Mendel: Researchers call for a new understanding of genetics*

Research

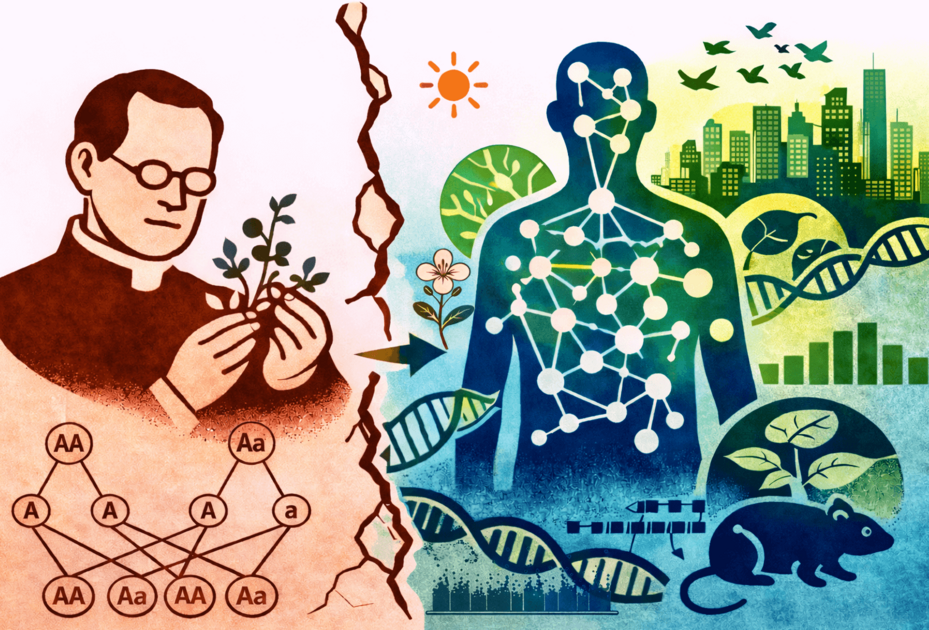

Beyond Mendel: Researchers call for a new understanding of genetics*

A perspective article in the journal Genetics argues for an experimental paradigm change to capture complex gene effects in combination with environment and genetic background. Co-author of this review publication is Christian Schlötterer, head of the SSFB project “Polygenic Adaptation” at the Center for Biological Sciences of Vetmeduni.

To the Point:

- Many traits and disease risks are not “one gene – one trait” effects, but emerge from the combined action of very many genetic variants.

- Classical single-gene models often fail to explain the variation observed between individuals when environment and genetic background come into play.

- The authors argue for new experimental paradigms and supporting infrastructure, including large-scale automated phenotyping and systematic studies including environmental change conditions.

For more than a century, Mendelian genetics has shaped how we think about inheritance: one gene, one trait. It is a model that still echoes through textbooks—and one that is increasingly reaching its limits. In a perspective article published in the journal Genetics, an international group of leading geneticists and evolutionary biologists calls for a fundamental shift in focus: away from searching for isolated, clearly defined gene effects and towards experimental approaches that treat genetic complexity not as noise, but as the starting point.

Their central argument: most biological traits—from morphology and physiology to disease risk—arise through the interplay of very many genes. Individual variant effects tend to be small, highly context-dependent, and strongly shaped by environmental conditions as well as an individual’s broader genetic background. Evidence from quantitative genetics, evolutionary biology and breeding research now converges on a shared conclusion: simple single-gene models cannot account for the phenotype and its variation among individuals.

“Classical genetics has achieved tremendous progress in identifying individual genes with clear molecular functions,” says Diethard Tautz, one of the article’s authors. “But with the approaches used so far, it has not been possible to explain the full phenotype—the characteristics of individuals as a whole in the context of their environment.”

This is becoming increasingly apparent in medical research. Many common diseases are influenced by a vast number of genetic variants within each individual. Each variant on its own may have only a minute effect; in combination—and in interaction with environmental factors—the cumulative impact can be substantial. The article traces the historical roots of this development, noting how twentieth-century experimental genetics deliberately concentrated on clearly defined single effects in standardised genetic systems. That strategy proved extraordinarily powerful for uncovering molecular mechanisms, but it runs into fundamental limitations when the goal is to understand individual variation, evolutionary adaptation, and complex disease patterns.

Against this backdrop, the authors call for a systematic development of experimental genetics. Future approaches should explicitly incorporate natural genetic variation, take evolutionary processes into account, and investigate genetic effects not in isolation but at the system level and within an environmental context. Proposed directions include parallel selection experiments, genome-wide analyses under controlled environmental shifts, and the study of natural adaptation processes in wild populations.

The FWF in Austria has taken a significant step in this direction. By funding a collaborative project on polygenic adaptation, it is connecting the world’s uniquely concentrated pool of experts in this field. “It is particularly the unique synergistic combination of theory and experiments that allows us to advance this line of research in a decisive way,” says Christian Schlötterer, head of the SFB project “Polygenic Adaptation.” The Institute of Population Genetics contributes expertise in experimental evolution using the fruit fly to the FWF consortium.

A key ambition of the paper is to catalyse the creation of suitable research infrastructures. Investigating polygenic trait architectures, the authors argue, requires large-scale, automated phenotyping—to be achieved through close integration of biology, engineering, and data-driven modelling.

The piece concludes with a clear message: genetic complexity should no longer be reduced away or ignored. It must be made experimentally accessible. Only then, the authors suggest, can we better understand both evolutionary processes and the biological basis of complex traits and diseases.

The article "Beyond Mendel: a call to revisit the genotype–phenotype map through new experimental paradigms" by Tautz et al. was published in Genetics.

Scientific article

*Press release by Max Planck Institute for Evolutionary Biology and Vetmeduni

Scientific contacts:

Univ.-Prof. Dr.rer.nat. Christian Schlötterer

Zentrum für Biologische Wissenschaften

Veterinärmedizinische Universität Wien

Christian.Schloetterer@vetmeduni.ac.at

Diethard Tautz

Emeritiertes wissenschaftliches Mitglied

tautz@evolbio.mpg.de

Max-Planck-Institut für Evolutionsbiologie